Culmination 2020

Winner

Christina Fishburne

"Outlaw," flash fiction

Runners-up

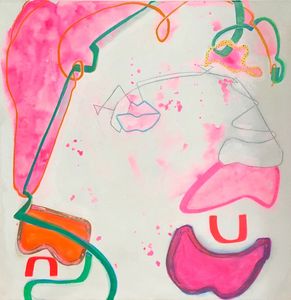

Barbara Rugg for “Droplets,” art (left)

Dean Gessie for “whitewash,” poetry

Finalists

Jasmine Kapadia for “wet pavement,” poetry

Amanda Bermudez for “Lacquer,” short fiction

Leah Dockrill for “Tuckamore,” art

Sarah Louise for “Real Life,” short fiction

Marieken Cochius for “Oumuamua,” art

Roxanne Bodsworth for “Mardungurra,” poetry

Abbigail Rosewood for The Void of Cards, novel

Inception 2020

Winner

Melisa Casumbal

Our Beloved, a novella

Runner Up

Dallas Frederick

"Pica Nuttalli—Yellow-Billed Magpie" (artwork; left)

Finalists

Frances Gufan Nan for “Tell Me the Textures You Were Made to Forget”

Dean Gessie for “[sick]stemic”

Aylah Ireland for "Matrilineal Cubes" (artwork)

Janet Garber for "The French Lover’s Wife"

Andy Carpenter for "Blood Creek"

Christie Cruise for "Pash" (artwork)

Drew Smith for “Out of the Mojave”

Laurie Babcock for “Student Affairs”

$100 for 100 Words or Art 2020

Winner

Alice Dillon

In These Uncertain Times (artwork on left)

Alice Dillon is a fiber artist from Worcester, Massachusetts. Her roots in fiber art trace back to receiving a sewing machine as a gift in middle school, which she used to create small projects. Alice began actively identifying as an artist in college when she taught herself how to embroider. Her embroidered works range in style from highly detailed to cleanly linear. She has recently become interested in repeated linear imagery, which brings a modern androgyny to a classically feminine medium. Alice is a graduate of Clark University, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in art history and history and a Master’s degree in history. She is one of ArtsWorcester’s 2020 Material Needs Grant Recipients. She is currently utilizing the grant to create life-sized, full-body embroidered portraits to be exhibited in 2021.

Winner

Karen Walker

Willow Widow

A willow grew unbidden in my backyard, flattering me with shade.

But the roots that crept under the fence proved insatiable. The tree’s slender silver leaves sympathized, agreeing that virgin soil and a fresh spring should have been enough, and pointed which way the wind now blew. A conspiracy of branches, each one as thick as a man, soon blocked my view.

I cut the willow down when green shoots—curly-headed like my little one—appeared all over the neighborhood. Until I find another tree (this time choosing wisely at the garden center), baby and I will plant flowers around Daddy’s stump.

Karen Walker writes short fiction and flash in Ontario Canada. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in online magazines and anthologies including Spillwords, Reflex Fiction, The Brasilia Review, Commuterlit, and Blank Spaces. People say Karen is fun and frustrating, and her chicken lasagna is pretty good.

Runner Up

Church Goin Mule

Time A Grand And Final Judge, Grow Bravely In Love (artwork)

Church Goin Mule is a southern outsider artist. You can find their work online at churchgoinmule.com, and on instagram @churchgoinmule.

Runner Up

Kameko Lashlee Gaul

Duology (poem)

Kameko Lashlee Gaul is a poet and pacifist from Olympia, Washington. She enjoys skinning her knees, feeling in extremes, pining, yearning, and the color blue. This is her first ever literary journal submission.

A Single Word 2020

Runner Up

CLAIRE LAWRENCE

VIRAL (artwork on left)

Claire Lawrence is a storyteller and visual artist living in British Columbia, Canada. She has been published in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and India. Her work has been performed on BBC radio.

Claire’s stories have appeared in numerous publications including: Geist, Litro, Ravensperch, and Brilliant Flash Fiction. She has a number of prize-winning stories, and was nominated for the 2016 Pushcart Prize.

Claire’s artwork has appeared in Wired, A3 Review, Sunspot, Esthetic Apostle, Haunted, Fractured Nuance and more. Her goal is to write and publish in all genres, and not inhale too many fumes.

Runner Up

ETHEL MAQEDA

Ubuntu

Ubuntu is a Nguni[1] word derived from the philosophy “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” (a person is only a person through and because of other people). In other words, we can only be fully human when we acknowledge, accept, appreciate and nurture other people’s humanity. In practice, Ubuntu fosters group solidarity, compassion and respect for others and encourages and enables individuals to continually expand their circle of humanity to embrace and celebrate diversity.

Growing up in a township in a small Zimbabwean city, I was content that my humanness was complete and affirmed by my friends, family and the community around me, although my world didn’t extend beyond a thirty-kilometer radius until I was nine. Ubuntu for me then meant respecting everyone, especially my elders, and sharing food, home and clothing with the less fortunate. The Shona saying Avirirwa[2] (dusk has surprised him/her) was one I heard often then. It meant that strangers could knock on any door on an evening and ask for shelter for the night before carrying on with their journeys. They then became an aunt/uncle, a relative for life. Ubuntu also meant you weren’t to stare or point at people that looked any different to you or make them feel different. We played netball with a feminine boy we called mainini, a term of endearment meaning “mother’s young sister,” and didn’t think anything of it. It has apparently become unacceptable as the boy became an adult and someone decided that his femininity made him subhuman.

Nobody is born with ubuntu . . . these are communally accepted and desirable ethical standards that a person acquires throughout his/her life, and therefore education also plays a very important role in transferring the African philosophy of life.[3] Family, community and school education all played a role in the development of my ubuntu. Just before the end of the War of Liberation from colonial rule in 1979, I turned seven and the tips of my fingers could finally reach my ear over my head. This meant I could start school. This extended my understanding of my circle of humanity to include children from other villages and communities, from the mining communities around the city whose families were usually migrant laborers from Malawi and Zambia. I became aware that the world was a much bigger place, not just peopled by black people and white Rhodesians; that there were other Christianities, other religions, other ways of thinking and being. I began to understand that people from the same clan could support different political parties, that not all black people were agreed on what independence from colonial rule meant. I learned that some black people had fought on the side of the Rhodesians. Ubuntu is about accepting such painful truths.

In the following year or two after I started school, an uncle, who I hadn’t been aware existed until then, came home from exile, a place I didn’t know existed either, and brought me a beautifully bound and illustrated copy of The Arabian Nights. As I gradually to read, I became enthralled by the tales of peoples in far-flung places, who in so many ways were so alien yet in so many other ways were also familiar. By the time I reached secondary school, the insatiable appetite to explore as many different ways of being as there are in the world had so taken over my life that I had read everything I could lay my hands on. I also learned about the importance of being a good listener.

At twenty, when I travelled beyond the thirty-kilometer radius and went to university, my understanding of humanness was further enriched by meeting people from other parts of the country and the world. I lost my first family member to HIV/AIDS, moving it from my science textbook to real life, and I fell in love with a Japanese boy called Ken. I also continued to be interested in literature, geography, history and politics, and to feed my appetite by reading, travelling and meeting new people at every opportunity. My education not only broadened my view of what it means to be human, but also allowed me to embrace my Africanness with pride, to appreciate and celebrate human diversity and to negotiate my way through encounters with people who hold on to differences and make them the basis of their relationship with other people. I have been called a monkey a few times.

In today’s world, ridden with war, displacement, poverty, and disease which put our Ubuntu to test, it will do all of us good to remember to be kind, considerate, and compassionate. Ubuntu is about the common good of society, with humanness as an essential element of human growth.[4] By deduction, anything that puts the life and wellbeing of others in jeopardy is anti-human. It means, in these challenging times, not hoarding food, toilet roll or soap. and not disregarding calls to practice social distancing or self-isolation.

Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu!

[1] Nguni people are the Zulu, Ndebele, Xhosa, Sotho, Swati, Phuthi, Nhlangwini, Lala and Ngoni speaking peoples of Southern Africa who share a similar culture, traditions and beliefs.

[2] “Avirirwa” and “mainini” are Shona words. Many Zimbabwean children grow up in multilingual households.

The Shona people of Zimbabwe share a similar worldview to that of Nguni-speaking people and other African cultures.

[3] M. Letseka, “African philosophy and educational discourse,” in, P. Higgs, N.C.G. Vakalisa, T.V. Mda & N.T. Assie-Lumumba (Eds), African voices in education(Juta: Lansdowne, 2000), p 186.

[4] Elza Venter, “The Notion of Ubuntu and Communalism in African Educational Discourse,” Studies in Philosophy and Education, 23. 2-3 (2004), 149-160 (p. 149).

Ethel Maqeda is a writer originally from Zimbabwe, now resident in Sheffield. Her work is inspired by the experiences of African women at home and in the diaspora. Her work has been published in various issues of Route 57, the University of Sheffield’s creative writing journal, Verse Matters (Valley Press, 2017), Wretched Strangers (Boiler House Press, 2018), and Chains: Unheard Voices (Margo Collective, 2018).

Winner

HANNAH VAN DIDDEN

The Meaning of Free

Download the PDF of her winning entry below.

Hannah van Didden writes where the story takes her—usually somewhere dark but truthful; often beautiful. You will find pieces of her scattered around the world, in places such as Tahoma Literary Review, Crannóg, Southerly, Breach, Atticus Review, and Southword Journal. To see more of her work, visit her website.

The Meaning of Free

Themeaningoffree (pdf)

DownloadInception 2019

Cynthia Belmont

Runner-up (Essay)

Down in the wash, in the chalky railroad bed at the bottom of the canyon, we laid pennies on the tracks. No trains rolled the slick black rails. Smashed eucalyptus leaves cracked in the dust everywhere. We were small but we knew how to get back, by the path through the sudden oranges like fruit trees in a tapestry, to where the yucca started at the foot of Nanna’s hill. Glowing Valencias clustered around us, walking together up the quiet dirt rows, don’t eat, don’t touch, watching for snakes.

Our mother lived in the San Bernardino foothills above these Redlands orchards in the 1940s, and she was a ringleted blonde, a single child, she was never allowed down here alone. She told us the farmers used to fumigate the orange trees and tent them to keep the mist in. One time some children lifted a tent like a skirt to see underneath, and they were asphyxiated. The end....

Cynthia Belmont is a professor of English and writing at Northland College, an environmental liberal arts school on the South Shore of Lake Superior, in Ashland, Wisconsin. Her creative work has been published in diverse journals including Poetry, The Cream City Review, Terrain.org, Natural Bridge, Oyez Review, and Sky Island.

Elizabeth Marian Charles

Winner (Novel)

When she thinks back to that night much later, she will wonder if it was the hinge upon which her life turned, and if she could have changed things, how much else might have turned out differently. And then she will make herself another vodka martini and light a Salem because that’s useless now, all the imagining, and she has always prided herself on being a practical person.

But no, that isn’t true—she has always been eminently a dreamer, head in the ether. Or now am I thinking of myself?

Her name is Joann Frakes, and in December 1949 she is the publicity director at the Camelback Inn when the Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, comes to visit the United States for the first time. This is the story the newspapers will print: The Shah sees Joann across the room, red rose in her blonde hair, and sends an aide to ask her to dinner. They eat and dance into the night, and then she goes to bed, pretty head abuzz with the events of the evening. He stays for three days, playing tennis, swimming, riding horses, attending receptions, and then he is gone. A royal encounter, over as swiftly as it began.

The Shah of Iran’s first American date, Time magazine will say, a willowy blonde from Oak Park, Illinois.

Elizabeth Marian Charles is a recent graduate of the Arizona State University’s MFA program. Her work has appeared in Bird’s Thumb and Fiction Southeast, and is forthcoming in Minnesota Review and Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Vol. 4. She lives and writes in Texas.

$100 for 100 Words 2019

Pamela Sumners

Winner

Love Poem

Darling, while I was gone for the summer

you heated gas on the stove and burned

down the house, and darling, while I was

gone, you invited a snake pit into the kudzu

and they strangled every last flower we had.

This is what I had heard but when I returned

the house stood true against the falling sky

but one dog was dead and another ripped

in his throat. I know my people always said

you were a little cold-natured for a Southern girl.

It must be those Yankee Calvinist parents you had.

Pamela Sumners is a constitutional and civil rights attorney from Alabama. Her work was published or recognized by thirty journals and publishing houses in 2018 and 2019. She was selected for inclusion in 2018’s 64 Best Poets and had been nominated for 2019’s 50 Best Poets. She was nominated for a Pushcart prize in 2018. She now lives in St. Louis with her wife, son, and three rescue dogs.

Single Word 2019

Valyntina Grenier

First Place Co-Winner

Valyntina Grenier makes art on the side of life that insists, “Don’t Shoot.” Her poetry and visual art push the boundaries of representation and abstraction to create a vantage from which to view violence and prejudice. Her work has appeared in CatheXis, Bat City Review, Tulane Review, The Volta's Arroyo Chico and Spiral Orb. Find her at valyntinagrenier.com or Insta @valyntinagrenier.

Morrow Dowdle

First Place Co-Winner

To Russia with Love

On any given night, the stories flow

like the filthy Volga in which the children

would wash themselves after eating supper

from the garbage heaps. It might be her friend,

wrapped in a carpet on an apartment roof,

doused with gasoline and set on fire

over and over until she died, slow-cooked.

Or how the prior tenant had been axed,

and she and her mother had to scrub blood

before they could move in. Or how

the elderly neighbors kept their brother

in the freezer, feeding off him piecemeal.

Or how soldiers and police would rape girls,

and girls would hook for spare change,

believing they lost less than they gained.

I marvel at how she can appear intact,

when the world was a rabid dog,

people its bared teeth and claws.

I can forgive, then, how she stroked

my husband from knee to thigh,

high as we were on wine. I can forgive

my husband for wanting to taste

the lips, the cunt that knew trespass

before it knew love, yet still

found its way to love. It tastes

as sweet as it ever did.

Morrow Dowdle’s most recent publication credits include River and South Review, Dandelion Review, Poetry South, and NonBinary Review.She was a Pushcart Prize nominee in 2018. In addition to poetry, she writes graphic novels, most recently in collaboration with the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. She previously attended Emerson College’s MFA program in creative writing and currently works as a physician assistant in mental health.

Image Contest 2019

J. Ray Paradiso

Runner-up

A confessed outsider, Chicago's J. Ray Paradiso is a recovering academic in the process of refreshing himself as an EXperiMENTAL writer and street photographer. His work has appeared in dozens of publications including Big Pond Rumors, Storgy and Typishly. Equipped with cRaZy quilt graduate degrees in both business administration and philosophy, he labors to fill temporal-spatial, psycho-social holes and, on good days, to enjoy the flow. All of his work is dedicated to his true love, sweet muse and body guard: Suzi Skoski Wosker Doski.

Timothy Boardman

Winner

Timothy Boardman is predominantly a fine arts artist and printmaker with some design sensibilities. He’s currently a student at UNCG in Greensboro, North Carolina.